XOCHIMILCO

Ciudad de México (CDMX)

19° N, 99° W

This story begins not in Mexico, but far to the north. In the near distant past. In a flat Josefina Jesús-María shared with her mother in Ravenswood. Chicago. From the safety of her bedroom closet, Jo stayed awake, hiding, through the night, from La Llorona. Tormented with stories of the evil spirit, told by her aunts, Josefina’s young imagination began perceiving the haunting wails of the doomed woman within the cold walls of her bedroom. Must be said: Jo had no fear the dead. She could walk past the old Bohemian Cemetery at night while smiling at them all. But La Llorona hits differently. La Llorona has an agenda, which makes her dangerous. La Llorona’s influence is strongest at the water’s edge, which is why Jo avoided crossing the Chicago River on foot if she could. If she must, she’d turn-up the volume on her headphones and run as fast as she could across the bridge. Similarly, she had a rule of not approaching Lakeshore Drive after dusk. Reluctantly, young Jo did learn to swim in a Northside community pool. But she’d be damned if she was going to close her eyes when she swam underwater. Not with that bitch lurking. And the chlorine burned. Really fucking burned. But Jo wasn’t taking any chances. She wasn’t afraid. She was vigilant. Vigilant with bloodshot eyes.

But who is La Llorona? Good question. Especially since those who know her best refuse to speak her name. La Llorona is a boogeywoman of Latin lore. A New World Medea; a mother who drowned her children and will take yours too if they wander too far. Decades later, Jo remains driven to uncover the myth, dig her up, look her in the skull and tell her off. Ya jodete, bitch. Jo feels indebted to her younger self, the niña hiding in the closet. Indebted to fulfill the promise of unmasking her tormenter. To make the malevolent benign by shining the light of day upon its damned face.

Which brings us here. Xochimilco. On the outskirts of modern Mexico City. Xochimilco is an ancient floating city predating the arrival of the Aztecs (or as they referred to themselves, the Mexica). When later 16th Century visitors from Europe arrived at the lagoons in the Valley of Mexico, they would compare the extensive canals of Tenochtitlan & Xochimilco with Venice. The original settlers of these wetlands built chinampas: islands of jasmine branches woven together and tied to trees standing in the lake. Atop the branches would be soil where seeds were planted. Roots would reach beneath the soil and into the water below. Floating gardens emerged. Waterways became fixed between each chinampa. Floating gardens became floating cities. After the fall of the Aztecs, under Spanish rule, the lakes of the valley would be drained. Few of the old canals still exist. Those that do are here. Xochimilco.

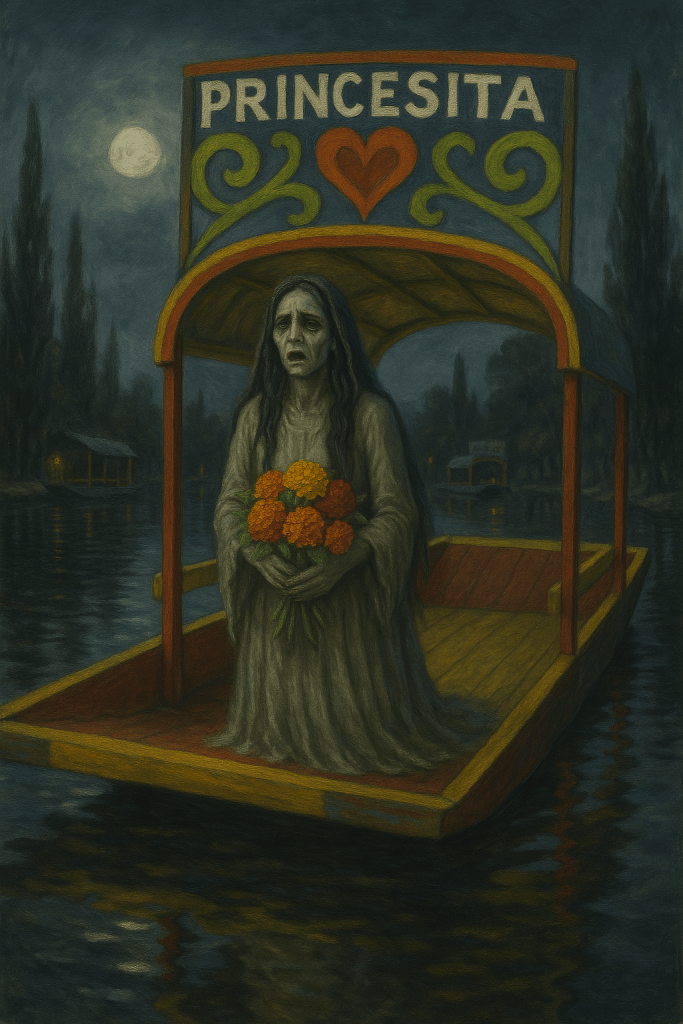

The uninitiated might confuse Xochimilco as no more than a park. Not wilderness, but a green realm of streams & gardens, intentionally sculpted by hand. Flowers are everywhere. Trajineras, the gondolas of Xochimilco, are decorated in outrageous warm colors and given passionate names like Princesita, Bonita, Chalupa. These boats are hired by families & lovers, especially today, domingo, when the after-church-mass picnickers are out in their Sunday best. At least a dozen trajineras are devoted to birthday parties. Specifically, quinceañeras. Those are not the screams of La Llorona, nor her victims, merely teenage girls in heavy gowns singing along to Beyoncé. Not all of the trajineras are hired by tourists: a third of the boats afloat in the canals are carrying musicians or food preparers or vendors of any sort. Along the journey we negotiate with the other boats for cafe de olla, elote, plenty of bottles of Corona, a few songs from a mariachi band, and the ancient elixir, pulque.

No, Vic, Josefina says to me, no pulque para ti. She tells Inocencio to purchase only three pulques. One for everyone, except me. Queque?, I cry out in my cave-man Spanish, porque no pulque para mi? Jo gives me a squint, daring me to distrust her judgment. Porque eres güero, Vic, she says to explain I am a white-boy. No ‘ombre, Jo says to me, stick to your cervesas. Besides, she says, you had plenty of mezcal with lunch. You will be fine. If you start drinking pulque, before long tu caga en la mierda. Jo’s comment triggers laughter from the smug lovebirds, Inocencio & his girlfriend, Inés. I glare at them, Ino y Inés. Fucking brats. Greedily slurping their pulque. What does that mean?, I ask Jo, “shit on the shit”?

Inocencio interrupts to speak Spanish to Jo in persuasive tones. His face is stifling a shit-eating-grin (sonrisa de comer mierda). Ay, Fina!, Ino calls to Josefina, deja que el güero beba. Let the gringo drink, he is saying. But I shouldn’t be fooled. Inocencio is no friend of mine. Nor does he have my best interests in mind. No. Inocencio only wants me to enjoy pulque so he can then watch me shit mis pantelones! Right here. On this boat. In front of Josefina y Inés!

Ino is young enough that his mustache hasn’t fully developed. And he has a whiny voice for being a big dude. He played back-up goalie on his collegiate futbol squad. Not during his one semester in Mexico City. No, Inocencio’s time in Mexico City was limited because he was too small of a fish in the big pond. Ino quickly returned home to continue studies in Tapachula where he was treated like the prince he preferred to think he was. “Don Inocencio” Josefina calls him in jest, chiding her kid half-brother for acting as if he were land-owning gentry despite living with his parents. Inés, Jo has explained to me, is from a Chiapas town smaller than Tapachula. She is a village girl, a Chiapneca easily impressed with Inocencio’s exploits, family name & liberal use of cologne. Good for him. Don Ino.

No ‘ombre, Jo says to Ino, Vic can smell the pulque, but he cannot taste. She says to me, pulque is made from agave like tequila and mezcal, but it sits in clay jars all day, fermenting. It’s got a lot of good gut bacteria, but your gringo tummy isn’t ready for this shit. Literally, Vic, Josefina says. You can drink pulque tonight when we’re back in Paseo de la Reforma. Somewhere near a toilet. And a bidet. Or a shower.

Fine. Claro que si. Bien.

The pulque appears to be thick & milky. Avena flavor (oatmeal). The cinnamon sprinkled over the top overwhelms the scent of the drink. And when Jo is distracted with flagging down a boat of mariachis, I take a sip from her cup. My tongue immediately rejects the substance, bulldozing it forward, but I close my lips before I go spitting-up all over our trajinera’s central picnic table. Jo turns in time to see an elongated face: my mouth is closed with tight-lips covering an open jaw. Like a cartoon cat caught with the canary. I swallow hard. And smile. Jo’s eyes are quizzical, re-calculating. Te amo, I say sweetly. I pop open a new Corona, gulping down the neck of the bottle in one go.

I like the pulque. I don’t want any more, but I like it. This might be the closest I ever come to knowing what necrophilia tastes like. It’s like yeasty… bubbly… funky saliva. Yeah, like kissing a corpse. I finish my cervesa in the hopes the beer drowns out the bacteria in the battle for my belly.

***Don’t try this at home, kids. Vic is a professional.***

I open another Corona by the time the mariachis begin their love songs. The band is playing from a boat tied-up to our port-side and those horns sound closer than they look. My bones rattle & reverberate. My gut is starting to quiver & hum. But I am resilient. After the mariachis, we’re visited by an elote dealer. I look at the warm cream this gondolier is pasting onto the corn cobs and decide on a hard-pass. No tengo hambre, I say.

Xochimilco’s most famous resident is the critically-endangered, cutest little salamander ever, the axolotl! Second-most famous, however, are the creepy-as-fuck dolls of Isla de las Muñecas. Yes. As seen on TV. On one of the old floating chinampa islands, Don Julian Santana Barrera built a shrine of dolls to appease the ghost of a drowned girl he arrived too late to save. Fifty years later, Don Julian himself was found face-down & drowned in the very spot where the girl had perished. Per his nephew, the last thing Don Julian said was that the mermaids of the canal were calling to him.

Our gondolier, Lucho, is willing to take us near the island, but not close enough for a landing. Many of the boatmen of Xochimilco are superstitious and remain wary of Isla de las Muñecas. Ino y Inés appreciate the caution. They are huddled together on the farthest bench of the traijnera, the blood having left their young faces. Josefina, however, has the same look of dogged determination I’ve seen before. Usually, it’s after midnight and she wants to sneak into a cemetery or an abandoned church. Fortunately, we can only gaze upon the island from afar. I do not dare look directly down into the water for fear of what might look back. I have a healthy respect for mermaids. Ever since being slapped by a mermaid as a boy in Florida, I’ve kept a wide berth. Legally, the slap was attempted assault & not battering. And technically, the mermaid was a manatee, but nevertheless, I steer clear of sea cows & sea hags, all the same.

Given the urban myths of vengeful sirens, it is no surprise to learn La Llorona’s spiritual home is Xochimilco. There is evidence of her legend in this valley predating the arrival of the Spanish. And every November 1st, Día de los Muertos, a play is performed before an audience of trajineras in the canals of Xochimilco: La Cihuacoatle, Leyends de la Llorona. The title of the play references both La Llorona and Cihuacoatle, an Aztec mother goddess, or “serpent woman”, and predecessor of the La Llorona myth.

While Mexican history is awash with larger-than-life men with big bigotes (Zapata, Jesús Malverde, Cantinflas, El Chapo), the crux of Mexican ethos is defined in its pantheon of motherhood. Most notably, the Virgin of Guadalupe. Her appearance before peasants at the nearby hill of Tepeyac, in 1531, began the mass conversion of indigenous Mexicans to catholicism. The image of Guadalupe is perhaps the most commonly seen in all of Latin America. Meanwhile, Cihuacoatle and/or La Llorona are tragic figures of motherhood often associated with another figure, La Malinche, the most flesh & blood historical of all these mythical mothers. And perhaps the most controversial. La Malinche was an indigenous Nahua woman, enslaved by Mayan and Spanish captors. She was the translator & mistress to Hernán Cortés, the conquistador who defeated the Aztecs and captured Mexico in the name of god & Spain. La Malinche would give birth to Hernán’s son, Martín Cortés, one of the first mestizos of mixed New & Old World blood. Renown for her treachery facilitating the conquest of Mexico, La Malichne is sometimes empathized by those who understand the few options she had. She was a slave to the Maya. What loyalty did La Malinche owe to the Aztecs? To anyone? Jack shit.

Yet, it is another mother altogether I find myself praying to on our return trip to port. Mayahuel. The Aztec goddess of fertility. And agave spirits. She’s the chick with the teats from which she feeds pulque to her 400 drunken rabbits. Mayahuel, I pray silently, please grant me intestinal fortitude. Please Mayahuel. Tell me what sacrifices I can make to satiate your fury. I feel her presence. I hear her in the grumbling of my tummy. She brings me hope.

I have faith. If I run out of faith, I might accidentally intentionally (whoa!) fall into the canal – damn the mermaids! – and from those depths, temporarily slip out of mis pantalones to complete the purge if that is what Mother Mayahuel demands. But for now, I have faith she’s more merciful than that.

Of course, fucking Lucho is taking his sweet time getting us back to the docks. Inocencio is bored & exasperated. Every exhale of his is a sigh or a groan. He is a reluctant host, ordered by his father to escort his estranged half-sister from Chicago around Mexico City. Josefina announces she’d like to visit a birria restaurant for authentic goat soup on the way back north, but Ino wants to be rid of us, the sooner the better. Jo doesn’t budge. Birria is non-negotiable. The boat ride back is tense.

From our far corner on the gondola, Jo mocks her half-brother Inocencio and his innocent girlfriend. You know what’s innocent?, Jo asks me. Babies. And puppies. Because they haven’t done anything yet. Jo says, that’s all innocence is: having done shit. Josefina is bitter. For good reason. While she was fatherless in Chicago, Inocencio grew-up in Mexico with their father’s security and, despite being much younger than Jo, he is in line to inherit the Jesús-María business & properties. Yet he lacks the grace to be a generous host for one goddamn afternoon.

Before Lucho can tie-up at the dock, I am leaping out of our trajinera, explaining my thirst and how I am going to seek out a bottle of water. This is a cover-story. I rush, running without moving my hips, to find el baño, paying a peso to the attendant for the slightest waft of tissue. I humble myself before the altar of Mayahuel. She, in return, grants me with an idea.

Having survived the ordeal, I travel with the Jesús-Marías to the birria restaurant. Ino y Inéz decide to sit at a two-seater table, which… fine by us. I’ve been thinking, I say to Jo over goat soup and beer. Dios mio, she says. When you grew up in Chicago, I say, you didn’t have any siblings or your father to look out for you. You were your own protector. And your mother’s. La Llorona was one more existential risk to be concerned with. But in the hypothetical that your mother never took you to the States and you grew-up in Tapachula, La Llorona might have actually become an ally to you, I say to Jo. She is intrigued. I say, once Inocencio was born to your father and step-mother, you would have recognized him as scoundrel early on and could have offered him as a sacrifice to La Llorona, bringing him down to the river, giving the chubby little dipshit a nudge…

How can you say that?, Jo asks me with the slightest glistening of her eyes. Her vein of rage rises from her temple. Her jaw loosens like a python. Do you realize?, she asks, how fucking sick you must be to even think that way? And then speak it into being? Planting the seed of fratricide in my head? How can I possibly unthink this? Damn it, Vic! You fucking, jagoff!

After a most uncomfortable silence, Jo bursts into laughing. She’s tormented with joy. An ill-timed laugh has resulted in her sneezing a little birria and there is now a greasy little red drip of goat soup peeking from her nostril. Ooh, it burns, Jo says with a napkin wipe. She cannot help from laughing. Do you think La Llorona would actually go for it?, she asks me.

Yeah! Of course! I mean… everybody wins! You get rid of your brother, La Llorona gets her sacrifice… Everyone wins, except the innocent.

Love the beginning creeps. Hooked!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Loved the history lesson. Step brother is a cad!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Half- brother, but yes! If Josefina got her fearlessness from her father, Ino must take after his madre.

LikeLike

so this drunk was sitting at the bar next to his pal wasted. “i dont know what to do, i’ve thrown up all over myself and my wife told me if i come home wasted one more time she’ll leave me”

”don’t worry” his buddy said “take a 20 dollar bill and put it in your blazer. tell her someone puked on you and gave you money for dry cleaning. easy “

when he returned home, he flung the door open to his waiting wife who was irate at the state of him.

he explained the 20 and she reached in his jacket pocket and pulled out 40.

what’s the other twenty from? she wanted to know.

“that’s from the guy who shit mi pantalones “

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perfect

LikeLike